An Op-Ed on the intersection of Culture and Sustainability in Ghana by Samata

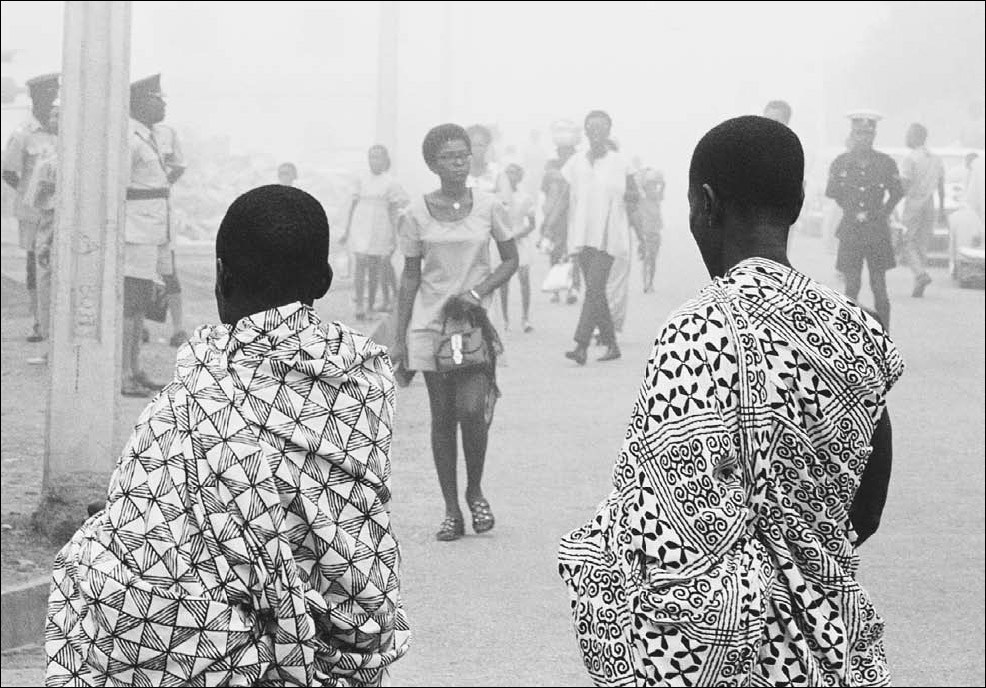

A multicultural phenomenon, the global fashion industry provides sustenance to designers from a plethora of cultural backgrounds. Exploring the lessons, traditional practises and cultural philosophies which might benefit the ethical fashion sector, I focused on Ghana, the birthplace of my parents. In doing so I wonder if the space where culture and fashion intersect provides progressive ground in the sustainable fashion conversation. Starting in Ghana, where clothing matters, and both expensive Western and traditional items are an important symbol of education and wealth.

Ghana’s Visual Eco Dialogue

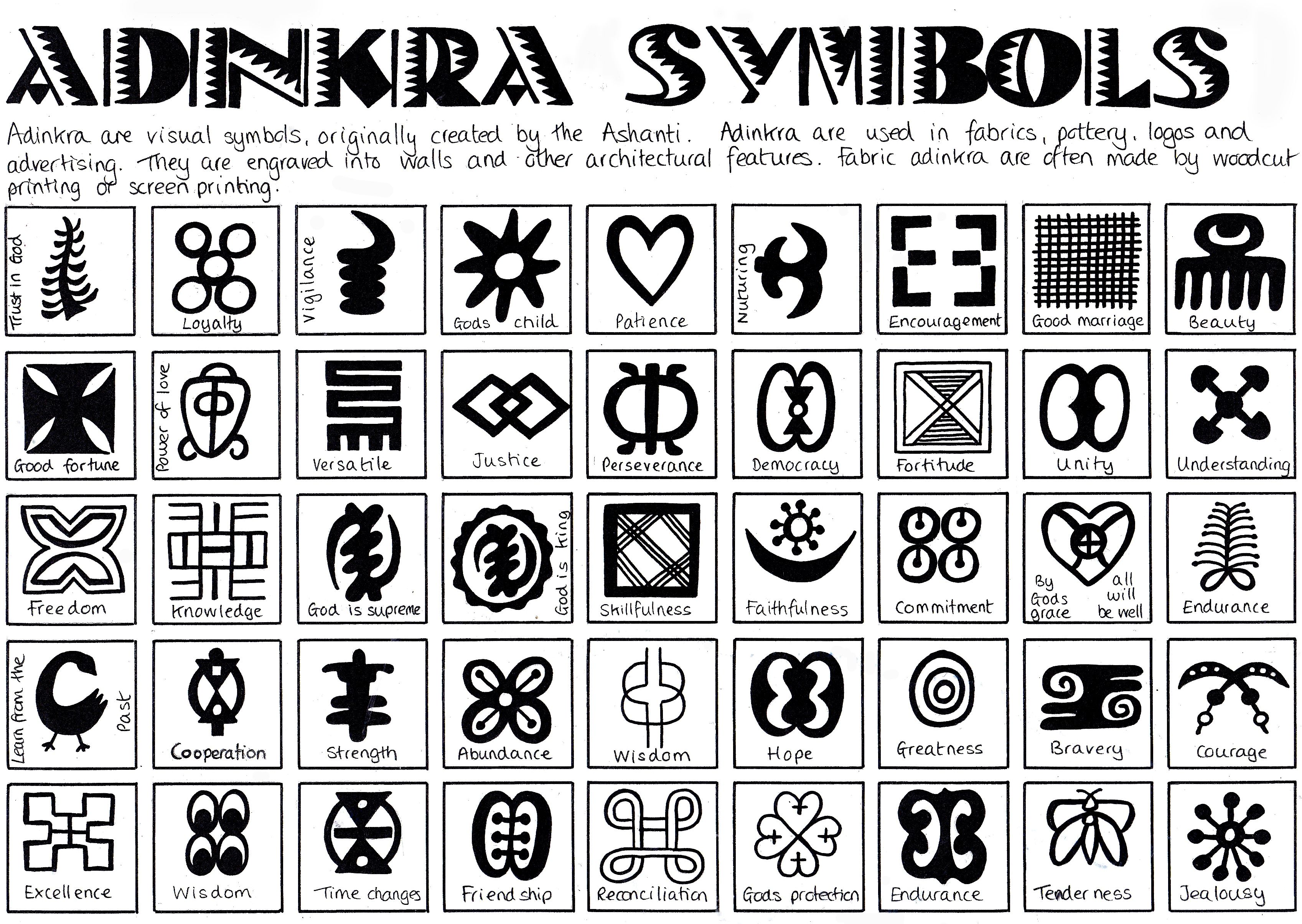

Fashion’s spotlight is on the culture-rich continent Africa – the sub-saharan market alone is worth $31 billion according to Euromonitor whilst Ghana, one of its 55 countries and known cultural gateway to West Africa, boasts an apparel and footwear market worth $167 million. Underneath the vibrant noise of the popular cotton wax prints, sustainability has always been an ongoing cultural conversation, and according to Kofi Laing, Joy 99.7fm radio host and Multi Tv’s fashion presenter, the Adinkra symbols – dating back to royal attire circa 1817 – prove it. “Adinkra is a sacred cloth using adinkra symbols, which are proverbs of advice relating to the proper conduct of the individual in society. Rooted in tradition and an inherent respect for the earth, Adinkra are used to express traditional Ghanaian proverbs, even commemorating anniversaries and elections.” A visual tool, the designs and patterns are a communicative statement printed on furniture, sculptures and clothing which both a literal meaning and philosophical message. Not your average statement tee, embroidered with traditional symbols this clothing often channels a message of sustainability.

The counterfeit Chinese textiles flooding the Ghanaian market – currently accounting for 60 percent of all textiles sold in Ghana – remain a challenge for authentic manufacturers such as Ghana Textile Products and Akosombo Textile Products, but the poor substitutes – inferior printing techniques which bleed on quick-to-fade poorly woven cloth – also run counter to the true essence of the Adinkra sayings, including calls for quality. Identified by four co-joining boxes, ‘Nsaa’ – also the actual name for a very high-quality cloth – symbolises authenticity, excellence and genuineness. “The proverb for Nsaa is ‘Nea onim nsaa na oto n’ago’, which means ‘The one who knows the nsaa blanket is willing to buy it, even when it is old’ – Nsaa is known for being of the utmost quality, and so the wider message is clear, only a fool would not want to invest in quality,” Laing explains. “Currently, there is a movement to preserve our local industry and to urge consumers to purchase only certified Ghanaian-made wax print.”

Adinkra symbols are carved into the surface of a piece of gourd, and stamped onto handwoven cotton broadcloth using a black natural dye made from the bark of the badie tree (Bridelia ferruginea). “Loyalty to old traditional ways maintains our tie with culture but also, through Adinkra’s visual dialogue, reminds the wearer of his/her debt to nature.” – ‘Asae’, another Adinkra symbol also reiterates the call for respect and social responsibility – “Adinkra cloth best expresses our traditional reverence for the earth and the respect she deserves. The Asae symbols offers sage advice about our relationship to earth, its’ proverb ‘Asase y3 duro se po’ translating to ‘The earth is heavier than the sea.’ It means we should give thanks to earth for the sacred gift of life, she provides us with shelter, food and incredible beauty.”

That these traditional prints can evolve and remain relevant is not even a question for Nana Yaw Designs founder and designer, Dennis Hunter, who believes sustainability is a dynamic mainstay in the Ghanaian fashion market, “Tradition is actually fluid by nature. There’s a fallacy to assume it’s static. Traditional fabrics will always be part of who we are; the look of the garments will change with time. So it’s a fluid sustainability.”

The Ghanaian Way

As the Gold Coast joined global Fashion Revolution Day activities in April, AAKS bag designer Akosua Afriyie-Kumi and country co-ordinator believes that culture provides a framework for inherently ethical practices,“We have a strong cultural practice in Ghana from funerals, to attending churches on Sunday to traditional marriage ceremonies which are widely celebrated.” Afriyie-Kumi, who is heavily involved in Fashion Revolution Day explains that during events like these sustainable decisions are par for the course, “Woven cloth which takes approximately 2 weeks to make in small villages, such as Bonwire in the Ashanti region, are sourced for such events.These are sometimes unconscious decisions made by customers towards helping the industry of hand made production and craftsmanship and general sustainable practices towards the fashion industry in Ghana.”

Laing co-signs, “Culturally, traditional pieces – bespoke and tailored – are carefully preserved, and handed down from generation to generation. This will always be part of the Ghanaian way of life”, asserting that whilst Western brands move in, the hunger for mass-produced fashion has not taken root here, leaving these culturally crucial heirlooms, bespoke tailors and super slick Ghanaian ready to wear brands like Christie Brown and social enterprise-driven Studio 189 (whose traditional batik promote artisan culture) to continue doing well. Even as the latest figures reflected that Ghana spent $65 million on importing used clothes from the UK (most charity shop cast-offs), quality remains king and treasured bespoke remains practical, “The second-hand garment industry has had a significant impact on West African countries, as used clothing is flooding markets and driving down the demand for bespoke clothing. On the other hand, in Ghana, a developing country, the majority of people work incredibly hard for a living so every garment made by a seamstress or tailor is expected to be carefully crafted in order to have a long life in the wardrobe of its owner. So in a sense we do follow the trend of ecological conservation as a matter of necessity.”

Created to perfectly fit the wearer with secret pockets to adjust for wear and body shape change over time, bespoke and tailoring are a dominant part of Ghanaian culture. “We tend to find a tailor or seamstress while we are teens, and that relationship follows our whole lives,” explains Laing. “It’s likely that the same seamstress who sews a girl a secondary school graduation dress will also sew her wedding dress, maternity clothes and even the dress she is buried in!” This intimacy streamlines efficiency for customers, creates a cherished piece and comes with a two way promise – for quality and fair trade. Could consumers in the West develop a similar relationship with smaller, independents brands, buying more keepsakes? Ones offering more bespoke service from the traditional offered by women’s only tailor Savile-Row tailor Gormley & Gamble to the high-tech online service offered by Sumissura and Proper Cloth? As Laing concludes, “There is nothing that can come close to a garment which is custom-made to the measurements of the individual. Ghanaians treasure this kind of quality, keeping these pieces for a lifetime.”